From a coastal ecosystem rich in fish and wildlife to an unproductive and degraded, acid-scalded landscape to a return to a flourishing wetland. The transformations were the result of human activities and it took deliberate acts of will and cooperation to restore ecosystem function and enable Yarrahapinni to become, once again, a healthy coastal wetland and a major contributor to the fishery and biodiversity of the Macleay Valley.

What once was

The area now known as Yarrahapinni Wetlands is located off Andersons Inlet, an arm of the Macleay River estuary on the NSW mid-north coast. It formed a unique coastal ecosystem within the floodplain as it was a complex estuarine system located between old dunes

The area was once ‘Yarr-ar-pin-ni’, the Country of the Dunghutti and Gumbayaggir nations, and was first occupied approximately 9000 years ago. It contains one of the largest estuarine midden complexes in Australia, consisting of 7 middens extending over 14kms, as well as a ceremonial site. It was a highly productive tidal estuarine wetland, with extensive seagrass and mangrove habitats providing important nursery habitats for many fish species, crabs and oysters.

With European settlement, the area became known as the Yarrahapinni Broadwater. Alongside its natural value, the area was also used for recreational and commercial fishing and oyster farming. The lower area of Yarrahapinni was known as ‘the Golden Hole’ due to its once abundant fish and shellfish.

The first transformation

It’s valuable land ruined by salt

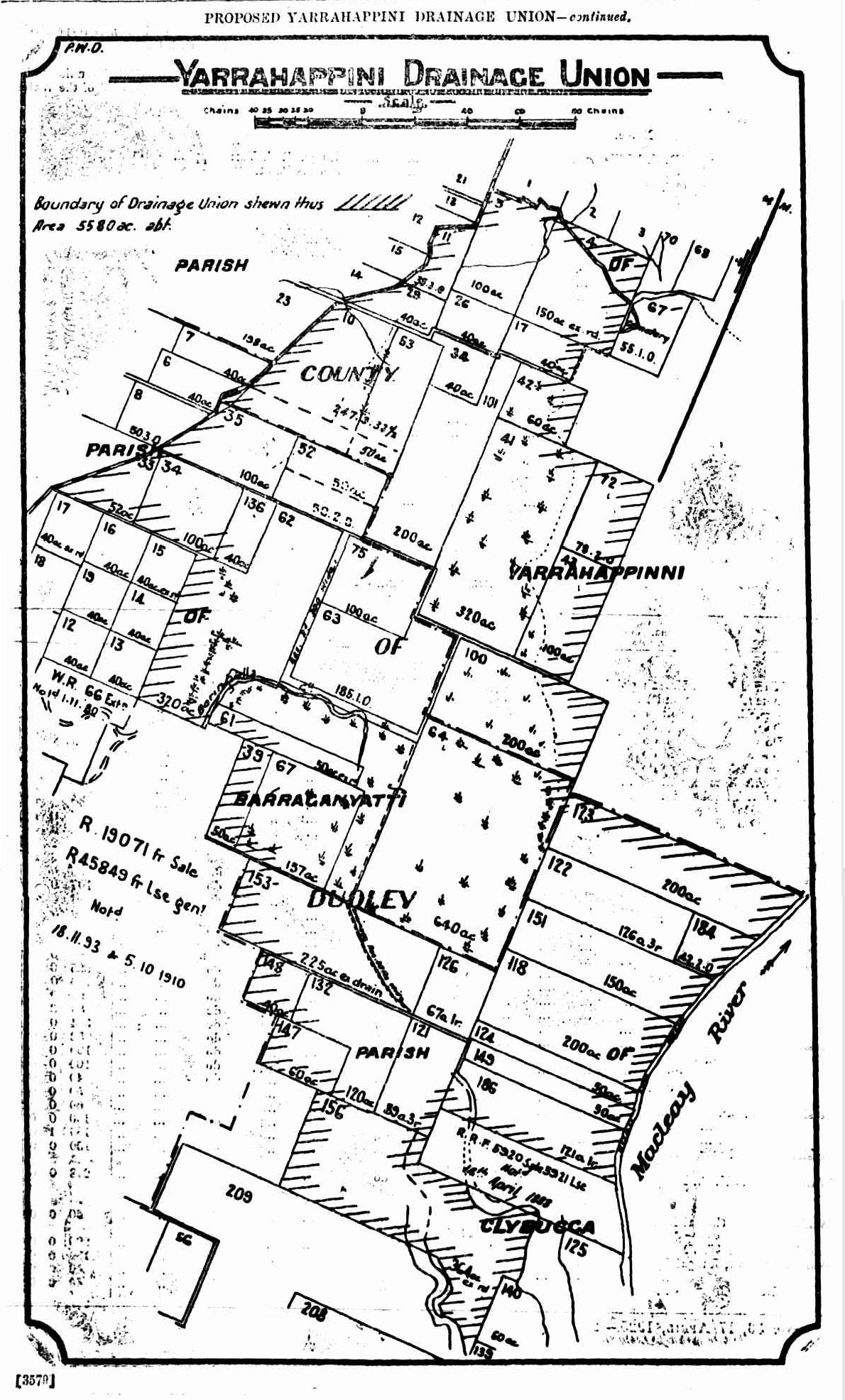

The first transformation occurred in the late 1960s, the culmination of a process that had begun in the early 1900s. As early as 1912, drainage of ‘the swamp’ was being proposed,[1] and by 1925 progress was being made on a Yarrahappini Drainage Union under the Water Act 1912 and auspices of the Kempsey Supervising Engineer.[2] It was argued that: insufficient drainage allows the water to accumulate and lie on the land, to the great detriment of its use for agricultural and grazing purposes and that the nature and cause of the accumulation of the water is due to the local rainfall and the flat character of the land … [3]

The argument was much the same in the mid-1940s. Newspaper reports of a meeting during which local Councillors argued for floodgates or embankments to ‘to keep the salt water off the land. There are thousands of acres of valuable land ruined by salt water there, and something should be done about it. … A floodgate would be best, as it would give you fresh water right down and get rid of the crabs.’ The Council moved to approach the Works Department to put a floodgate at the mouth of Broadwater, Clybucca and Yarrahappini Creek. [4]

By the late 1960s the decades of argument and lobbying led to the Macleay River County Council initiating a flood mitigation program to control the flow of water into the wetlands and assist in the management of small nuisance flood events. A levee wall and a five-floodgate headworks were installed, completely isolating the wetlands from tidal inundation. As a result, saline water was excluded, the water table lowered and the area slowly converted into a freshwater wetland.

A fishery lost

This resulted in significant losses to the fishery, a decline in biodiversity and a degradation of soil and water quality. Yarrahapinni Broadwater quickly became a degraded freshwater system discharging black water with low pH and low dissolved oxygen into once healthy commercial oyster leases and recreation and professional fishing grounds.

Part of the justification for the flood mitigation program was the expectation that agricultural activities would follow. The projection by the NSW Department of Agriculture was that 1200 hectares would be cleared and intensive stocking and cropping would commence. This did not occur. The land was, at best, marginal grazing country and any benefit derived from increased stocking rates was offset by the more rapid drying out and more frequent burning of the area, as well as the negative impact of soil and water acidification on pasture quality. [5]

The value of the wetlands as they were was not factored in when the decision was made to install floodgates and drainage. Regular tidal flooding created important food and nursery habitat for many estuarine dependent fauna, including the fish that supported recreational and commercial fisheries, helped to maintain potential acid sulfate soils in their neutral state, and provided an important food source for growing oysters in the adjacent estuary.

The loss of tidal input led to dramatic changes in the area of mangroves, saltmarsh and other estuarine vegetation. Mangroves declined from nearly 84 hectares in 1942 to 0.6 hectares in 1994. Saltmarsh over the same timeframe went from covering nearly 339 hectares to 3.6 hectares. Seagrass was lost altogether. The area became dominated by reeds and Swamp Oak (Casuarina glauca), interspersed with weeds, such as Groundsel, Lantana and Giant Parramatta Grass.

It wasn’t long before it became recognised that there was a serious problem emerging within Yarrahapinni. Lindsay Brackenbury has been a resident neighbour of the Yarrahapinni Wetlands since 1972, with 15 hectares of his property intruding into the wetlands. Lindsay recalls that approximately 18 months after construction of the levee and fitting of the floodgates from Andersens Inlet, the rear and largest part of his property was still covered by live mangroves and cleared muddy expanses of drying seagrass. In then turned into “Dried areas of exposed acid sulfate soils and other chemical bearing soils that resulted in a completely degraded and virtually useless extensive acreage of originally productive marine expanse for fish and crustaceans and shellfish” (Quote: Lindsay Brackenbury. Source: Kasmarik 2007).

As early as 1976, oyster growers were lamenting the flow of polluted water that was killing their oysters and were demanding that the Yarrahapinni Creek floodgates be opened.[5]It was estimated that $1.7 million annually of fisheries productivity had been lost due to the reduction in mangrove habitat in the Yarrahapinni system.[6] Studies showed greatly reduced fish diversity and numbers, no juvenile fish and no prawns compared to a comparable nearby estuarine area.[7]

An area known as ‘red dog scald’. Dried areas of exposed acid sulfate soils resulted in a completely degraded area which had been a productive marine expanse for fish, crustaceans and shellfish). Image: P. Haskins

Vegetation within Yarrahapinni became dominated by reeds and Swamp Oak. Image: Water Research Laboratory

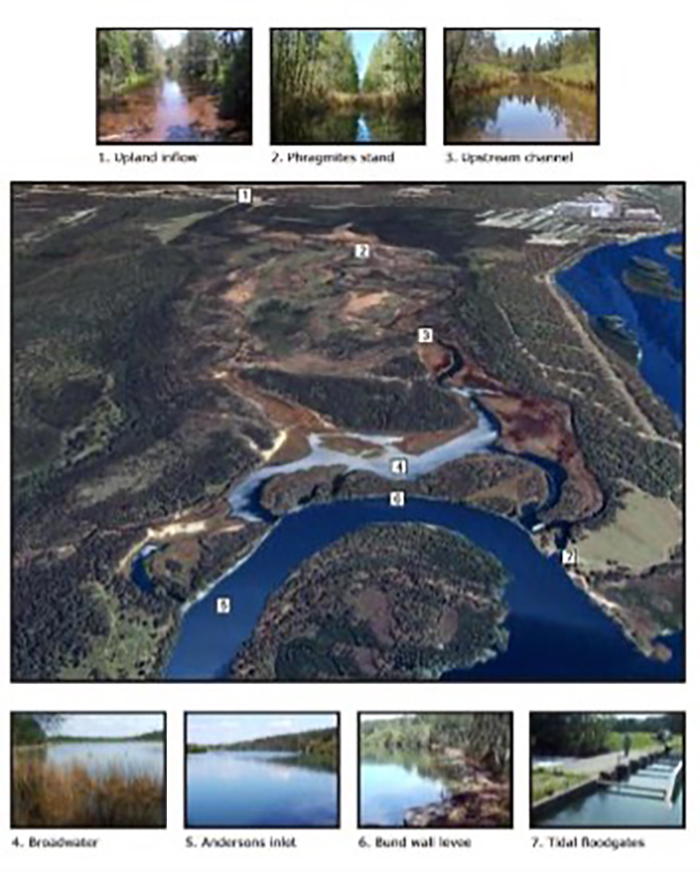

An overview of Yarrahapinni Wetland prior to restoration. Image: Water Research Laboratory.

No benefits

On the other hand, the drainage and flood mitigation changes to the Yarrahapinni wetlands provided no measurable benefits to agricultural productivity or flood mitigation. In 1980, an operational regime that included periodic flushing was suggested by the NSW Public Works Department

The situation by 1985 was such that even the NSW Department of Agriculture was saying that ‘If the presence or current operation of a flood mitigation structure cannot be justified then habitat restoration should be undertaken’. [5] Things were at an impasse and at the core of this were some of the landholders. Fisheries officers summarised the situation with: “The few private individuals using the land adjacent to and including part of the area are presently unwilling to see its conversion back to an estuarine condition. Although oyster farmers, fishermen, conservationists are keen for the area to be restored, the state government has been reluctant to make funds available in the face of opposition from the landholders”. State Fisheries formed that view that the State agencies tasked with managing fisheries and lands were going to have to take the initiative.

In 1986 the Department of Fisheries published a paper that was critical of structural flood mitigation works and highlighted the impact on estuarine environments. The paper drew attention to the loss of the once-famous ‘Golden Hole’ and pointed out that Macleay oyster farmers had suffered mortalities of 50 – 80 percent and fishers had noted the detrimental effects of flood mitigation works on fisheries production. [10]

Undoing what was done … progress, politics, floodgates & foolishness

Legal hurdles, confusions and machinations

Ownership and the other 1/10th of the law

It became apparent that the ownership of the floodgates was itself a point of confusion. In May 1998, the Trust learnt that the floodgates were on the Clybucca Historic Site, managed by the NPWS. However, Council had always considered that they owned the gates based on handover documents from Public Works from 1972. Ownership became irrelevant however, when, on 13 May 1998, four of the five gates were illegally removed, resulting in 6-days of tidal exchange.

When is a wetland not a wetland?

The legislative hurdles pivoted around the State Environmental Planning Policy 14: Coastal Wetlands (SEPP14). SEPP14 was designed to protect coastal wetlands identified as such when the planning policy was enacted. It was not recognised that some areas were not in their natural state: Yarrahapinni was not naturally a freshwater wetland, it was estuarine, but it had been identified as freshwater within SEPP14. In addition, the change to Yarrahapinni had led to Casuarina glauca (Swamp Oak) becoming a dominant species. By the time restoration was proposed, Swamp Oak Forest had been listed as a Threatened Ecological Community under the then Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, which complicated any process designed to return the area to its original condition. Council’s interpretation was that opening the area up to tidal flows and estuarine water would cause the freshwater post-1971 regrowth to be ‘cleared’ within the meaning of the SEPP.

Legal interpretations and misinterpretations

The SEPP requirement meant that a Development Application (DA) had to be submitted to Kempsey Shire Council, accompanied by an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The EIS was completed in 1997. Unsurprisingly, Council received objections to the DA, including from landowners that could be affected. In addition, Council also asserted that the Trust was not a ‘public authority’, and therefore had to obtain the written consent of all the landowners.

1998 brought further legal ambiguity. Council indicated to the Trust that modifying the management of the floodgates and the resultant effects in areas outside of the SEPP 14 wetland would require separate assessment – that is, a separate DA and EIS. In addition, the Trust was advised that it would also have to comply with the new Native Vegetation Conservation Act 1997, which had come into force on 1 January 1998, because the opening of the floodgates would effectively lead to ‘clearing’ of existing vegetation. This was later retracted because the clearing was not separate activity from that covered by the DA.

The potential for acid sulfate discharges led the Trust to understand that a licence to pollute would be required from the Environment Protection Authority.

In another twist, the Trust’s plans for a boardwalk through the lower part of the wetland were thrown into confusion when the Department of Urban Affairs and Planning imposed a condition that Casuarina glauca be rehabilitated, with 10 Casuarinas to be planted for everyone destroyed. This was despite the fact that the trees had only invaded the area since the exclusion of saltwater, and would die off once the gates were opened.

On the other hand, another Endangered Ecological Community, Coastal Saltmarsh, which had once been present but had since almost disappeared from the area would be assisted by any reinstatement of natural tidal flows. In addition, ‘Alteration to the natural flow regimes of rivers and streams and their floodplains and wetlands’ is listed as a Key Threatening Process (KTP) under the Threatened Species Act,1995 and the ‘Installation and operation of in-stream structures and other mechanisms that alter the natural flow regimes of rivers and streams’ is a KTP under the Fisheries Management Act. The rehabilitation activities would mitigate these KTPs.

It was decided to withdraw the DA from Council. Major hurdles, what appeared to be a lack of interest from key State Government agencies particularly planning and environment agencies and a definite lack of funding had stymied progress and frustrated both trust members and community supporters.

A way forward

Late 1998 saw new funding and new advice. The Trust was advised that it was, in fact, a public authority for the purposes of the various pieces of legislation and this had two significant implications. One, permission was not required from landholders to lodge the DA and EIS; and two, Kempsey Shire Council could not refuse the DA or impose conditions without the Minister’s consent. So, with a few revisions, the DA was re-submitted. By 2000 Yarrahapinni Wetland Reserve Trust’s proposal was accepted, with the condition that a Management Plan, incorporating a Wetland Management Plan, an Acid Sulfate Soil Management Plan, and a Contingency Plan, be prepared.

A Plan of Management for the Yarrahapinni Wetlands Reserve was developed in 2001. This provided the strategic and legal framework the guided the Trust’s management of the site and its rehabilitation. The goals were wide, ranging from ‘to rehabilitate and maintain the full biodiversity of the Yarrahapinni saltmarsh mangrove wetland systems for the long-term protection of wildlife and habitat values’ to ‘to facilitate low-impact eco-tourist and recreational uses of the wetland’ and ‘to understand and protect the significant Aboriginal cultural heritage values and landscape values of the wetland’.

Stage 1 of the Yarrahapinni Wetland Rehabilitation Project was officially launched with the opening of one floodgate on 17 May 2001 by the Minister for Land and Water Conservation.

Gates opened but then shut

The trial opening ended up being complicated. The gate was opened and shut several times, in response to rainfall, landholder complaints and another unauthorised opening, this time of a second floodgate. The gate was closed less than 18 months later.

Both the local Council and the NSW Department of Planning were raising novel issues relating to the consent to restore the wetland. Council was being threatened with lawsuits by landholders if the gates were opened again and by oyster growers if they were not.

The following table provides a time line of events in the life history of the rehabilitation of Yarrahapinni wetlands.

The Minister’s opening of the floodgate, with the comment to the assembled crowd that they were: “witness[ing] an event many said would never happen. The joke about Yarrahapinni being in reality Neverhapinni can be put behind us once and for all”. (Image source: Tulau 2016)

Buying back the farm to bring back the fish

2003 saw a change in direction following serious water quality issues in the lower Macleay that resulted in fish kills and mass oyster mortalities. Serious consideration was being given to put the administration and maintenance of the wetland and floodgates in the hands of the National Parks and Wildlife Service. The benefit of such a transfer was a compelling one: development (such as re-watering a wetland) on land reserved under the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Act could be carried out without development consent from the local Council. Late in 2003, the Department of Lands gave its consent for the transfer of the Yarrahapinni Wetland Reserve to the NPWS for inclusion in the national park estate.

As ever, things were not straightforward. There were funding issues and the Trust itself was left somewhat in limbo. It wasn’t until October 2005 that the first NPWS land acquisition took place, greatly assisted by a private donation of $500,000 received by the Trust for the Yarrahapinni Rehabilitation Project. It took until March 2011 before all the land parcels that needed to be purchased were secured.

A legal transformation … and some fish at last

The area was gazetted as National Park in March 2007, with a total area of 806 hectares. This ended the role of the Yarrahapinni Wetland Reserve Trust. In its place, the Yarrahapinni Wetland Working Group was formed, working under the auspices of the NSW Department of Environment and Climate Change. Given the experience and local knowledge of trust members, some remained to contribute to the working groups efforts to see the trust’s work continued.

The installation of two tidal fish passage gates on the floodgates in December 2007 enabled partial tidal exchange in the lower reaches of the wetlands and fish passage, as well as some much needed water exchange for the wetlands.

The fish responded.

Prior to the opening of the floodgates, there was 70 – 80 per cent fewer estuarine-marine species of fish and crustaceans found in the area compared with other, nearby ‘reference’ creeks that had not been floodgated. After the opening of the floodgates, the number of fish and crustacean species increased and become more like that found in the reference creeks. Following the opening of the floodgates that number of species of estuarine-marine fish and crustaceans doubled, then doubled again in the subsequent 8 months. There were School Prawns, Yellowfin Bream, mullet, gobies, and glassfish. The response of the freshwater-estuarine fish varied, with some increasing in abundance, such as the Pacific Blue-eye and Flathead Gudgeon, and some decreasing. This monitoring did not detect significant changes to the salinity or dissolved oxygen, but there was a small increase in pH.

The monitoring showed that the fish and crustaceans respond rapidly to the restoration of tidal flushing, even when, as in this case, it was only partial. In 2008 a hydrologic investigation of the site was conducted and informed the development of a restoration plan for the Yarrahapinni Wetland National Park . It was recommended that the site be rehabilitated through the removal of the floodgates and levee banks using a staged approach. It was recognised that the wetland was unlikely to return to its historical state immediately, however, rehabilitation in and of itself would bring about significant benefits.

The priorities for restoration were to restore the hydrology or tidal influence to a natural state. This would foster the return of a healthy estuarine wetland ecology. Re-inundation was considered an effective and cost-effective solution to manage the many environmental issues that had arisen with the end of tidal flows, including those associated with Acid Sulfate Soils. The site needed to evolve naturally back to its condition representative of what it was like pre-1970 even though this would be a longer-term approach.

In February 2010 one of the tidal gates was opened entirely. The floodgates remained in place in case blocking of tides was needed for some reason. The gates that were opened were chosen carefully to minimise any damage that might occur to the banks now that the tides were flowing in and out and in the event of floodwaters draining from the site. Additional land was also purchased to allow the natural retreat of the Swamp Oak Forest in response to the re-inundation. The staged timing of the gradual re-inundation meant that this ecosystem would have time to migrate to the new area.

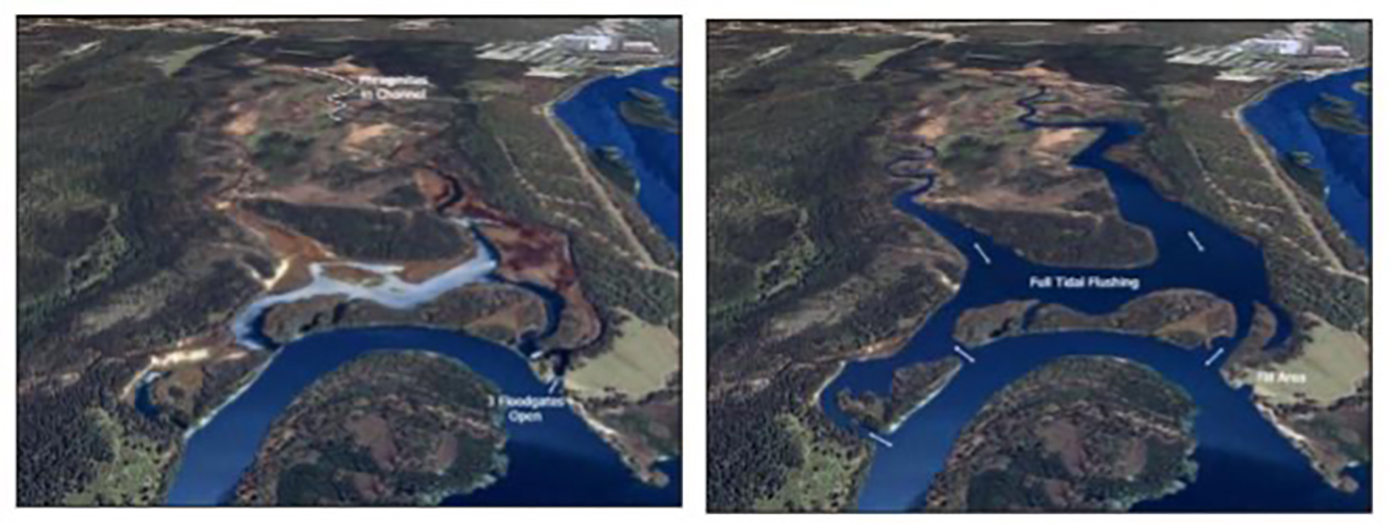

Once the detailed hydrological assessment had been completed (in 2011), it was recommended that the Yarrahapinni Wetland National Park be rehabilitated to a tidal wetland using the following staged approach.

Step 1. Opening of all five floodgates, allowing greater tidal exchange within the Yarrahapinni Wetlands.

Step 2. Partial removal of the western portion of the levee to enable tidal inundation of the wetland system. Doing this largely restores the hydrology of the wetland.

Step 3. Removal of the remaining portions of the levee and closure of floodgates.

Left Image: Initial efforts involved the installation of two tidal flushing gates, allowing partial tidal exchange. Image: Water Research Laboratory.

Right Image: What a fully restored hydrology for the wetland looks like. Image: Water Research Laboratory.

The second transformation … a work in progress

The second transformation … a work in progress

The plan

The goals of the 2001 Plan of Management for the Yarrahapinni Wetlands Reserve were reflected in the 2013 Yarrahapinni Wetlands National Park Plan of Management. Management actions targeted staged restoration of the natural hydrology and rehabilitation of the degraded ecosystems, especially saltmarsh as well as the provision of educational, recreational and cultural opportunities. The Implementation Plan indicates that much progress is yet to be made. It gives high priority to implementing the rehabilitation plan contained within the 2009 Yarrahapinni Weltands National Park Restoration Plan.

In September 2016 complete removal of the Yarrahapinni floodgates was commissioned. This included removal of floodgate infrastructure – the gates would not return. Without maintenance and with the power of the tides the man-made levee banks also succumbed to the ebb and flow of a natural tidal regime.

The permanent removal of the gates and the infrastructure that supported them (left; photo: M. Riches) enabled the free-flow of water (middle; Photo: M. Tulau). The natural flows soon eroded the levee (right), furthering the restoration of the wetlands (photo: M. Riches).

While the wetland will continue to find a balance the efforts and perseverance over many decades by many dedicated and passionate people has led to the foundation facilitating full rehabilitation being achieved.

Members of the Yarrahapinni Working Group inspecting the results of decades of trials, effort, frustrations and, finally, transformations (Photos: M. Riches).

Yarrahapinni wetland and the flora and fauna that are so intrinsically linked to its health are now managed for their conservation value. While it has taken decades and many people have come and gone over that time, some disillusioned, some frustrated and some have given up, many of the people involved have had great determination and perseverance in not giving up on the goal of returning the tide and health to the wetlands. At times the political, financial planning and legal obstacles seemed insurmountable. However, as the Yarrahapinni story can contest, staying the course, taking the odd strategic withdrawal, being strategic and flexible in project management and mobilising and acting when the time is right can never be underestimated in achieving great things.

The transformation of ‘red dog scald’: 2009 (left); 2013 (middle) and 2016 (right) (Photos: M. Riches).

Toxic iron release from poor management of acid sulfate soils – 2008 Photo: Stuart Johnston

Stories from the new, old wetland

With the natural ecological processes and services returning so too has the Aboriginal cultural significance of the site has also returned. Aboriginal communities associate natural resources with the use and enjoyment of foods and medicines, caring for the land, passing on cultural knowledge, kinship systems and strengthening social bonds. Aboriginal heritage and connection to nature are inseparable from each other and need to be managed in an integrated manner across the landscape.

The Yarrahapinni Wetlands are situated in the country of the Dhanggati and Gumbaynggir nations, and it is acknowledged as a sharing place for the two Aboriginal groups. A number of other tribal groups are likely to have visited the area for a range of cultural practices, including people from the Ngamba tribe. Cultural camps are now returning bringing the dreaming into the relevance of today, in order to begin the returning of true way of being.

As with the wetlands the Dhanggati and Gumbaynggir nations have begun their story of ‘Gaarrawaygam’, The Returning.

Your stories

This is one of the most significant wetland restoration projects that have occurred in Australia both in terms of scale and environmental, social and cultural outcomes. It is really important to document the past value, its degradation after the gates went in and its current beauty. Do you have a story to tell? Or a photo to share? Please contact us at info@ozfish.org.au with Yarrahapinni in the subject line and we will make sure this story is updated.

Acknowledgement

This story was researched and written by Dr Liz Baker after trawling through over 40 years of NSW DPI Fisheries letters, minutes and other documents, and edited by Marcus Riches.

Making a Difference

This story tells you that this restoration project was highly complex. It would not have happened with the commitment and passion of a group of NSW public servants, Council staff and local residents who believed that the Macleay River and its community would reap significant rewards for its completion.

Thank you to all!

References and sources

Boys, C.A., Kroon, F.J., Glasby, T.M. and Wilkinson, K. (2012) Improved fish and crustacean passage in tidal creeks following floodgate remediation, Journal of Applied Ecology, 49: 223-233.

Geolink (2010) Macleay River Estuary Management Study.

Glamore, W.C. and Timms, W.A. (2009) Yarrahapinni Weltands National Park Restoration Plan, WRL Technical Report 2009/05, The University of New South Wales Water Research Laboratory, Manly Vale.

Glamore, W.C., Wasko, C.D. and Smith, G.P. (2011) Rehabilitation of Yarrahapinni Wetlands National Park: Hydrodynamic Modelling of Tidal Inundation Report, WRL Technical Report 2011/21, The University of New South Wales Water Research Laboratory, Manly Vale.

Graham, J. and Duggin, J. (2004) Yarrahapinni Wetlands Vegetation Monitoring Final Report, Yarrahapinni Reserve Trust.

Foundation for National Parks & Wildlife 15-Mar-2008 http://www.hotfrog.com.au/business/Foundation-for-National-Parks-Wildlife_1291805/A-New-Park-to-Restore-a-Wetland-9319

Kempey Shire Council:

https://www.kempsey.nsw.gov.au/Your-Valley/Your-environment/Waterways/Coast-estuaries-wetlands

Middleton, M.J., Rimmer, M.A. and Williams, R.J. (1985) Structural flood mitigation works and estuarine management in New South Wales – case study of the Macleay River, Coastal Zone Management Journal, 13(1).

Office of Environment and Heritage (2013) Yarrahapinni Wetlands National Park Plan of Management, NSW Government, Sydney.

Smith, R.J. (1991) ‘Rehabilitation of the Yarrahapinni Broadwater – Macleay River’, Paper later presented to the Wetland Conference, Grassy Head Field Study Centre, September 1996.

Shepherd, M A. (1993) The effects of flood mitigation structures on fish and prawn communities in Yarrahappini (sic) Broadwater, Macleay River, NSW. School of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University.

Tulau, M. (2016) Lands of the richest character: agricultural drainage of backswamp wetlands on the North Coast of New South Wales, Australia; development, conservation and policy change: an environmental history, PhD thesis, Southern Cross University

Endnotes

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/174478623

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/220256044

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/223031061

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/173613937

- Smith 1991

- North Coast Environment Council (NCEC 1999)

- Shepherd

- Middleton et al 1985

- CaLM 1992, as reported in Tulau 2016.

- Boys et al 2012

- Glamore and Timms 2009